Jewish Calendar

There are many things that non-Jewish visitors to Israel find fascinating and also perplexing - the list is long but can include kosher dietary laws (why can’t you mix milk and meat?), Shabbat laws (why doesn’t public transport run from Friday night to Saturday night?), Yom Kippur (why does the whole country shut down for 25 hours, even the airport?!) and the nature of the state itself (if the state is ‘Jewish’ then do Christians and Muslims have the same rights as Jews?)

Sevivon, a spinning top, played during the Jewish holiday of Hanukkah. Photo by Robert Zunikoff on Unsplash

These are all good questions, and deserving of good answers, but there’s another question too, that many people ask, again and again, which we’re going to discuss today. That question is ‘Why is the Jewish calendar different from calendars used in most of the West today?” Well, let’s take a closer look at the historical events in Israel and the history behind Jewish dates, and why the Hebrew calendar (‘Ha Luah Halvri’) differs in any respect from the Gregorian one.

Hopefully, by the end of this article, you’ll even be able to tell locals what Hebrew month your birthday falls in, and why Jewish holidays such as Pesach, Rosh Hashanah, and Hanukkah fall on different ‘Western’ dates each year. Put simply, the date of these Jewish holidays doesn’t change i.e. it's celebrated on the same day of the Jewish calendar each year, but because the Jewish year works on a different basis to that celebrated by most of the world, the date will always shift on the ‘Western’ (civil) calendar.

Matzoh-crusted chicken for Passover. Photo by Sheri Silver on Unsplash

The Biblical Period

From the earliest of times, peoples and countries in West Asia, including the Israelites, made use of the Babylonian calendar. This was ‘lunisolar’ in nature - it consisted of 12 lunar months, each of which began at sunset on the day a new crescent moon was cited. Additionally, a thirteenth month was added - as needed - by decree (more of this later).

The Babylonian calendar took its shape from the Umma calendar of Shulgi, which dates back to around 21 BCE. By 6 BCE, with the Jews in captivity by the Babylonians, the names of their months were incorporated into the Hebrew calendar.

By the Tannaitic period (10-220 CE) an additional month was added every 2-3 years to ‘correct’ (or at least account for) the difference between the solar year and the twelve lunar months. This additional month was usually added depending on agriculture events in ancient Israel.

By the 12th century, Maimonides - one of Judaism’s greatest sages - addressed the issue in his book ‘Mishneh Torah’. He ruled that the world was created on October 6th, 3761, according to the narrative of creation in the Book of Genesis. All of his rules for this calculated calendar (with its scriptural basis) are used by Jewish communities throughout the world today.

Religious Jews against the background of Jerusalem walls. Photo by Arno Smit on Unsplash

How the Jewish Calendar Works

Essentially, the Jewish calendar is based on three astronomical events - the Earth rotating on its axis (one day), the moon revolving around the earth (a month), and the revolution of the earth around the sun (a year). On average, it takes 29½ days to make a month and 365¼ days to calculate a year, which comes out at about 12.4 lunar months.

Now, the civil calendar (in use in Europe, North America, Africa, etc) has long since abandoned the idea of correlating the moon cycles and months - instead, the lengths of various months have been set (somewhat arbitrarily) at 28,29,30 or 31 months. However, the Jewish calendar coordinates all three of these astronomical phenomena - its months are either 29 or 30 days (in line with the 29½-day lunar cycle) and years are either 12 or 13 months (in line with the 12.4-month solar cycle).

Western Wall, Jerusalem, Israel. Photo by Ondrej Bocek on Unsplash

When does the lunar month begin in the Jewish calendar?

This begins when the first ‘sliver’ of the moon becomes visible after the sunsets. Historically, this would be determined just by looking at the sky - when Jews saw the new moon, they would notify the Sanhedrin (a kind of ‘Supreme Court’, universally acknowledged by Jews). Once two of its members had listened to testimony from two eyewitnesses, who they deemed to be reliable, they would declare ‘First of the Month’ (‘Rosh Chodesh’ in Hebrew).

This shows that the Jewish (Hebrew) calendar is lunisolar, as opposed to the Gregorian (Roman) calendar, which is linear and works around the date of Jesus' birth. The Jewish calendar's months start and finish according to the moon - when the crescent’s center leans right and gets bigger every day, it’s the beginning of the month. By the time it is full, it is the middle of the month and when the crescent leans light and becomes slimmer, this shows that the month is concluding.

Of course, the problem with this is that the lunar calendar is slightly shorter than the solar calendar, so the year ends up becoming shorter. (Actually, according to the Lunar calendar in Islam, holidays such as Ramadan can be held in winter one year and in summer a couple of years later). However, because the Jewish calendar places great emphasis on nature and agriculture, it is deemed important that the holidays fall in the same seasons each year.

The star of David with Blossoms on a fruit tree in spring. Photo by David Holifield on Unsplash

The Months of the Jewish calendar

Here are the 12 months of the Jewish calendar: Nissan (March - April), Iyar (April- May), Sivan (May - June), Tammuz (June - July), Av (July - August), Elul (August - September), Tishri (September - October), Cheshvan (October - November), Kislev (November - December), Tevet (December - January), Shv’at (January - February), Adar (February-March), Adar II (every 3 years), February - March.

In Jewish leap years (which occur seven times in a 19-year cycle, which amounts to approximately once every 3 years) an additional month of Adar is added (Adar II). This ensures that the lunar months align with the solar year and that the Jewish holidays continue to fall in their proper seasons.

When do Jewish days actually begin?

In the west, a new day begins at midnight. But that’s not the case in Judaism. According to Jewish law, the day begins with the appearance of three stars in the sky. This is because, in the first book of the Hebrew Bible - Genesis - in the first chapter, which describes the creation of the world, it is said: “And there was evening and there was morning…one day.”

Thus, Jews argue, first was evening and only afterward the next day. This is why Jewish holidays always begin at sundown - and why the Jewish Sabbath ‘’Shabbat’) begins Friday evening and ends Saturday evening. According to Western culture, each day begins at midnight.

Freshly baked (challah) bread. Photo by shraga kopstein on Unsplash

Why does the Jewish New Year Begin in September or October?

The Jewish (Hebrew) calendar begins with Rosh Hashanah (which means’ First of the Year’) and this always falls on the first day of Tishrei (the seventh month), which is some time in September or October. Fun fact: the Jewish calendar actually has several ‘New Year’.

Nissan 1 - for the purpose of counting the reigns of Kings and months), Elul - for the tithing - voluntary contribution/taxing - of animals, Shevat 15 - for trees, determining when the first fruits of the season can be consumed. Tishri 1 - the new year for years.

The Jewish Year - Why is it Only in the Five Thousand?

The Jewish calendar’s specific year number represents how many years have passed since creation. It’s important to remember that for the most part, Jews do not use the terms ‘AD’ and ‘BC’ to refer to the years in the civil calendar.

This is because Jews do not believe Jesus is Lord, ergo would not want to use terms such as ‘Before Christ’ and ‘Anno Domini’ (Latin for ‘In the Year of our Lord’). This is why Jewish scholars will always use the terms ‘BCE’ and ‘CE’ which refer to the Common Era, before and after respectively.

An Orthodox Jew against the background of the red wall. Photo by Carmine Savarese on Unsplash

So what year is it in the Jewish calendar?Currently, the Roman year is 2022 because, according to them, Christ was born 2022 years ago. However, because Jews do not believe that Jesus was the son of God, they, therefore, count the years from what they believe was the creation of the world. This means that, according to Jewish calculations, the year 2022 is currently 5782.

The years of the Hebrew calendar are always 3,750 or 2,761 greater than the Gregorian calendar - and why this discrepancy? Because the number of the Hebrew New Year always changes at Rosh Hashanah, in the Autumn/Fall, rather than on January 1st. Of course, this leads to a huge debate between theology and science, since most scientists regard the beginning of the universe as commencing with the ‘Big Bang’.

Roughly speaking, that is around 13.8 billion years ago! How do Orthodox Jews account for this disparity? It’s a good question and the fact is that many will freely admit that the first ‘six days’ of creation did not necessarily occur in 24-hour periods (particularly because, according to Genesis) the sun was not created until the fourth day!)

As a result, they say, these ‘days’ of creation were actually much longer periods of time. They could have been ages or even periods lasting billions of years. As some Jews remark, “A billion years to man might be like a mere day to God.” This is a way, perhaps, to get around the current discrepancy between the Bible and science, although no doubt the debate will continue to rage.

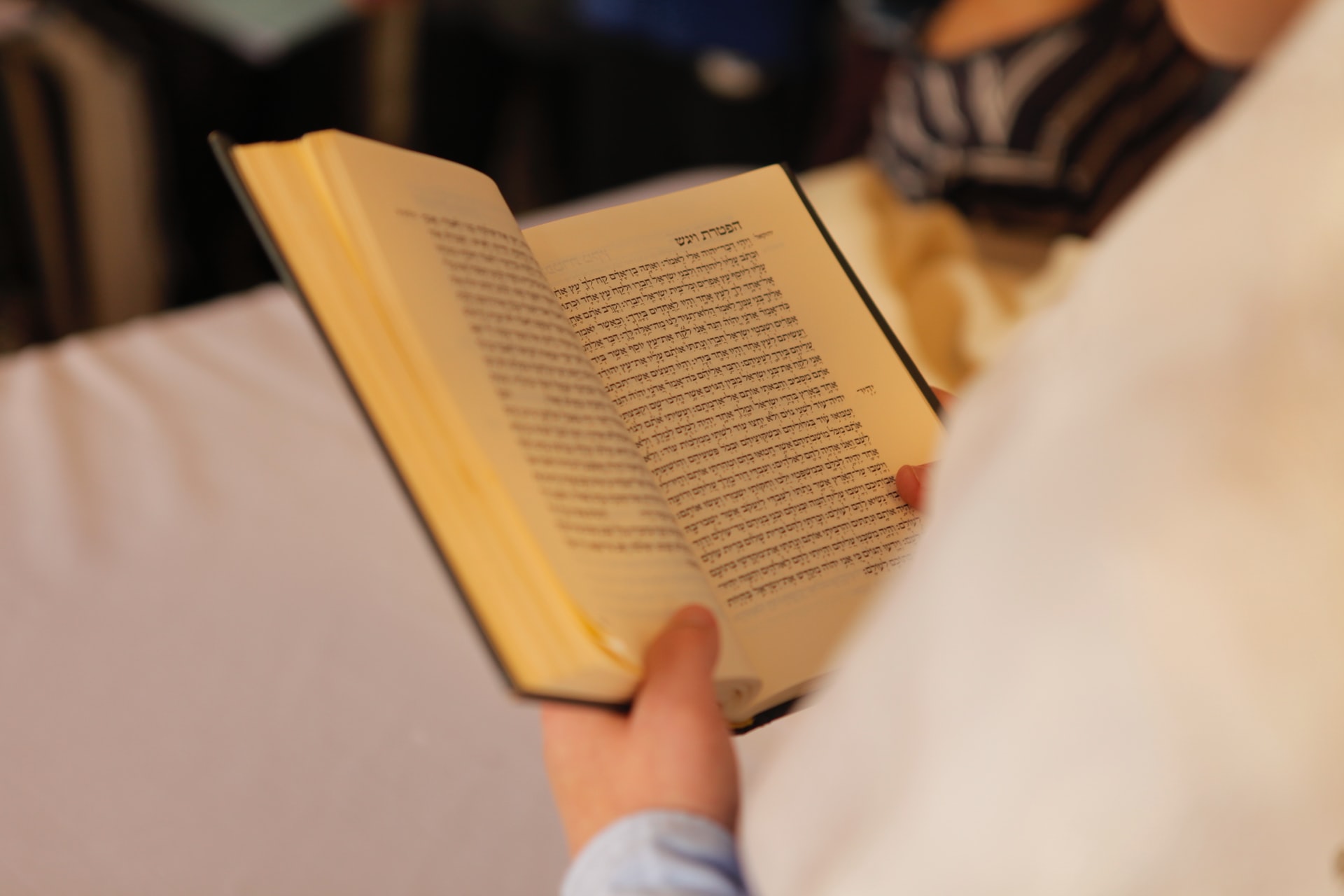

Weekly Torah reading. Photo by Eran Menashri on Unsplash

Are there any other Jewish calendars in use?

This is an interesting question and the answer is ‘yes’. Outside of mainstream Judaism, there exist smaller groups who use calendars based on the above practices, but with some differences.

The Karaite calendar

Karaite Judaism differentiates itself from mainstream Jewish beliefs in that it recognizes only the written Torah as the basis for religious law (Halachah). Karaites believe that all of the commandments that God gave Moses on Mount Sinai were recorded in the written Torah alone. Therefore the Oral Torah (which takes its form in the Talmud) and other interpretations of Jewish law are not considered binding by Karaites.

The Karaite calendar uses the lunar month and the solar year, but there are two major differences. The first is that the beginning of a new month - Rosh Chodesh - is contingent on the sighting of a new moon so, if for any reason, it is not sighted, then it will be put back a day. Karaites also differ from the mainstream in that they calculate the leap year - Adar II - by the ripening of barley at a certain stage, which means they can occasionally end up one month ahead of their counterparts.

Star of David. Photo by Benny Rotlevy on Unsplash

The Samaritan calendar

The Israelite Samaritans trace their lineage back 127 generations within the Holy Land, adhering to the laws of the Torah and reading the scriptures in ancient Hebrew. Rather than a rabbi at their pulpit, they usually have a ‘High Priest.’ Their calendar is similar to the Jewish one, with the main difference being when its starting year is. Traditionally, it was calculated on observations of the moon, as mentioned earlier in this article.

However, whilst mainstream Judaism takes the day of creation (as told in Genesis) as its first day, Samaritans count day one as the day the Israelites entered the Promised Land with Yehoshua Bin-Nun. Consequently, they are not completely synchronized, and, as a result, after a cycle of 19 years, the Samaritan festivals take place one month after the mainstream Jewish festivals.

The Qumran calendar

The Dead Sea Scrolls (discovered accidentally by a shepherd boy, in Qumran, in 1947) make several references to a calendar used by the people who lived there in ancient times - the Essenes. It seems that they used a Mesopotamian system of twelve 30-day months, and then added on four days at the solstices and equinoxes.

This amounted to 364 days in a year, in all, which meant that after a few years their calendar would have been seriously out of sync with the seasons. No one really knows how the Essenes dealt with this - whether they regulated it or simply ignored it!

We hope you’ve got something out of this article, and now understand a little more about Jewish festivals and why they fall when they do in Israel. If you’re interested in learning more about Jewish history in Israel, why not consider taking one of our Jewish tours, giving you the chance to see important sites and learn more about the heritage of the Israelites.

The Qumran caves, Israel. Photo credit: © Shutterstock

Login / Register

Login / Register

Contact Us

Contact Us

Certificate of Excellence

Certificate of Excellence Guaranteed Departure

Guaranteed Departure Low Prices Guaranteed

Low Prices Guaranteed 24/7 Support

24/7 Support