The History of the Hebrew and Yiddish Languages in Israel

When you arrive in Israel, one of the first things that will strike you is the letters of the Hebrew alphabet! You’ll see them on storefronts, menus, banners at Ben Gurion airport, and all kinds of public transport. The letters in this alphabet (referred to by scholars as Jewish script or ‘Ktav Ashuri’) certainly can puzzle visitors (luckily for them, the Roman script is widespread too!)

A historic Old Testament scroll rescued from the city of Lodz in Poland. Photo by Mick Haupt on Unsplash

Early Hebrew was the alphabet used by Jews before the 6th century (basically the Babylonian Exile) and existed in local variants. For sure, it developed over time but essentially it had - and still does - 22 letters, but only with consonants represented. The letters are written in block form. Just as interestingly for the visitor, it was - and is still - written from right to left. And it’s not the only language in Israel you’ll see written this way either - Arabic (although written in cursive, not block letters) and Yiddish are also written right to left.

As we all know, language is an incredibly powerful tool in society - it helps people communicate with each other, build relationships, and also enables them to promote their culture. Language lets people share common ideas, express feelings and desires, and, in turn, forges all kinds of ties between people. And never more so than in Israel which was in the interesting position of only having revived Hebrew (in its modern form) in the last 150 years!

Today, we’ll be looking at language in Israel - how linguistic scholars and Zionists alike promoted a Hebrew revival and how this Hebrew revival impacted Yiddish speakers (many of whom had come to Palestine/Israel from Eastern Europe and knew nothing of Hebrew, save for what they could read in the Bible). We’ll also take a look at how Yiddish is still used in small religious communities in Jerusalem and how it’s even making a bit of a comeback amongst the young and secular in wider Israel. Let’s go! Lamir Geyen! ! בוא נלך

A wall at Netiv HaAsara facing the Gaza border reads the words “Path to Peace” in Hebrew, Arabic, and English. Photo by Cole Keister on Unsplash

Hebrew From Ancient Times until the 19th Century

Historically, ‘square’ (block) Hebrew was established in the land of Israel, some time between the ½ BCE and slowly developed into what is now the modern Hebrew alphabet, in the next thousand years. By 10 CE, classical Hebrew existed in three clear formats - formal (used in books), rabbinical (used by medieval Jewish scholars), and local scripts.

So actually, Hebrew had roots that dated back a long time, which makes the story of it being brought back to life even more extraordinary. As mentioned earlier, 150 years ago Hebrew was not a spoken language - it was effectively dormant and used simply for prayer. Only because of Eliezer Ben Yehuda - an individual of exceptional vision - was it brought back from life. How did he do it?

A Hebrew Revival

Ben Yehuda was born in Lithuania and arrived in Israel (then Palestine) in 1881. Settling in Jerusalem, he heard many languages around him - Russian, Polish, Arabic, German - and soon he took the view that these new arrivals needed a common tongue to unite them. As a Jewish nationalist.

Ben Yehuda believed both in the return of Jews to their historical homeland (the Land of Israel) and a ‘national tongue’. To make the latter challenge a reality, he decided to transform ancient Hebrew - used just for prayer for thousands of years - into a modern language. Ben Yehuda campaigned vociferously for Hebrew to be made the official language of instruction in schools and set to work expanding the existing Hebrew vocabulary.

He created more than 300 new words (including ‘toy’, ‘car’, ‘ice cream’, and ‘newspaper’). He also dedicated himself to compiling the first modern Hebrew dictionary and later edited the first Hebrew-language daily newspaper. On a personal note, Ben Yehuda was a stickler for discipline and, in schools today, every Israeli child hears the story of how he only spoke Hebrew to his own children (even when they wept). In fact, his son Ben Tzion was the first child in modern times to grow up using this language as his mother tongue because of his father’s sheer determination.

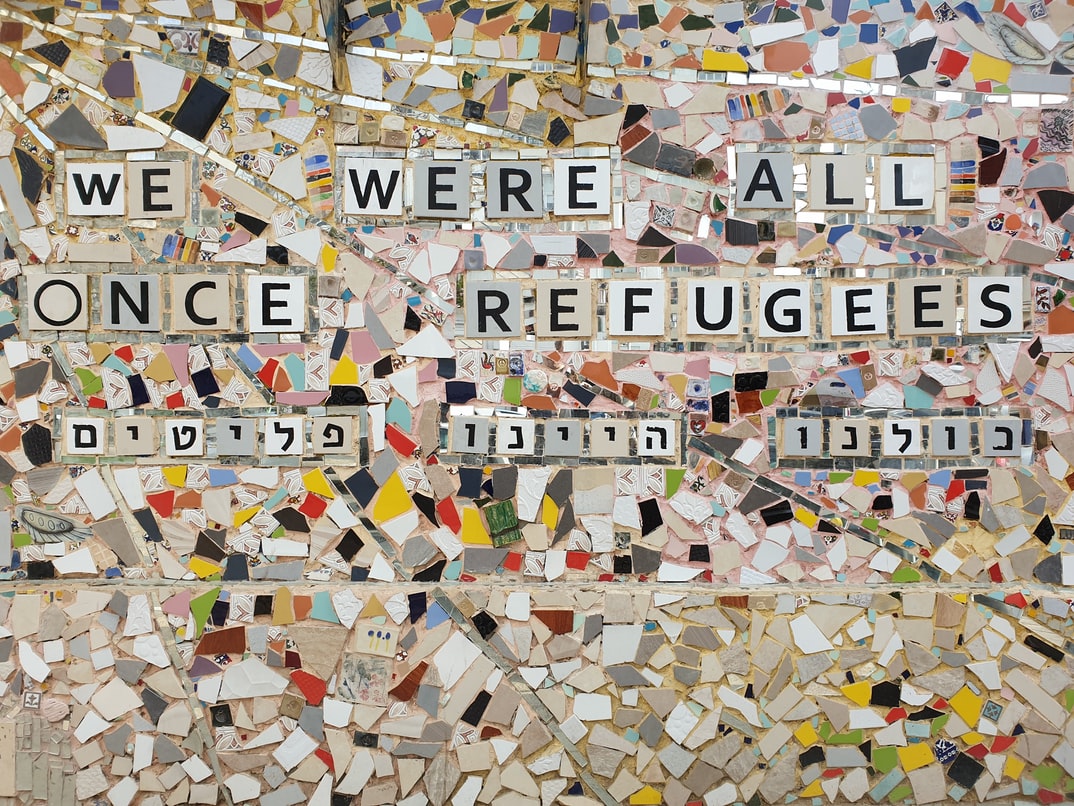

Mia's Mosaics "We Were All Once Refugees". A collaboration with Kuchinate, a Women's African Refugee Collective, Tel Aviv. Photo by Antoine Merour on Unsplash

Hebrew as the national language of Israel

Thanks to Ben Yehuda’s sterling efforts, more and more communities of Jews who had arrived in the First Aliyah (1881-1903) and the Second Aliyah (1904-1914) established Hebrew schools in their surroundings. As a result, by 1922 there were enough Jewish pioneers speaking Hebrew in their daily lives that the British Mandate rulers recognized it as the official language of Jews in Palestine.

Since then, modern Hebrew has developed a lexicon of more than 75,000 words including almost 2,500 deliberately designed Hebrew alternatives for foreign words. Whilst Ben Yehuda himself never lived to see the creation of the State of Israel, this idea of the Jews speaking their own language in their own land came to pass.

Arguably, this made him one of the most successful language revivalists of all time as well as one of the most prominent historical figures in Israel! Today, modern Hebrew (or ‘Ivrit’ as it’s called) is the standard form of the Hebrew language spoken in Israel, and every new immigrant who arrives is offered, courtesy of the government, a free ‘ulpan’ which is a language instruction program, teaching them the basics.

Road sign in Haifa in Hebrew, Arabic, and English.Photo by Levi Meir Clancy on Unsplash

So what is the Yiddish language?

Today, in every school, restaurant, and business place in Israel you’ll hear Hebrew spoken. But as well as the fact that it was only adopted ‘officially’ 100 years ago, there’s another reason Hebrew wasn’t widely spoken back then - it’s because Yiddish was incredibly common. Yiddish was the language of Ashkenazi Jews - Jews who hailed from Central and Eastern Europe.

Written in the same alphabet as Hebrew, by the 19th century Yiddish was spoken widely in any community in the world where a Jewish population existed. The history of Yiddish is indeed a fascinating one. Scholars have traced its origins back to the 14th century when Ashkenazi Jews emerged as a community in Europe.

From its birthplace, in German-speaking areas, it eventually spread to all of Eastern Europe. A fusion of High German (‘Hoch Deutsch’) vernacular and Slavic words (especially Polish and Ukrainian) it even has a historical trace of Romance language expressions in it. Yiddish is an incredibly rich language, as a result, even having what is called ‘artificial loanwords’.

This actually means that the word borrowed from elsewhere and used in Yiddish doesn’t even exist in the original language. A good example is ‘tate-mame’ which means ‘parents’ in Yiddish. (And not to forget about Yiddishe mama). In Slavic, these two words mean ‘dad’ and ‘mum’, but there’s actually no such phrase in Polish (or, indeed, any other Slavic language).

As a result, many of the Jews who arrived in the Holy Land (then Palestine) spoke Yiddish as their mother tongue. They came from all walks of society - writers, politicians, business leaders, artists, social activists - and they were devoted to their language. This, of course, would become problematic for them as time passed, since they were also Zionists, therefore felt obliged to promote the Hebrew language in its new, modern format.

Orthodox Jews in Jerusalem. Photo by Arno Smit on Unsplash

Hebrew vs YiddishBetween the first aliyah and the creation of the State of Israel, therefore, Yiddish was spoken widely, although as time passed, modern Hebrew became predominant. However, Yiddish culture was alive and kicking in all kinds of forms - on the stage, in music venues, and in European-style cafes on Tel Aviv’s trendy Dizengoff street.

So what changed this? Essentially, a huge cultural and ideological shift in Israel in the 1940s and 1950s. after the unspeakable horrors of the Holocaust. After millions of Jews had been murdered in the camps, the remaining survivors began looking for new homes. Some went to North America, others to Europe, and some even to Australia but many, of course, set sail for Israel.

The then-Prime Minister, David Ben Gurion, had made a decision not to turn away a single refugee, in his quest to bring Jews from across the globe to this new homeland. But not, as Ben Yehuda had also said, to be a collection of different peoples - to forge a new country and a new national identity. This didn’t just mean having Hebrew as the official language of the state, it meant actively encouraging Yiddish speakers to abandon their ‘mamaloshen’ (mother tongue).

Ben Gurion’s vision (and that of many of his contemporaries) was to create a new identity for the Jews - strong, proud, and ideologically committed. He encouraged immigrants from Eastern Europe to forget the ‘shtetls’ (villages) where they had been raised, and ‘shake off’ everything to do with their old lives.

Candles from Safed with inscriptions in Hebrew, Israel. Photo by Joshua Sukoff on Unsplash

It was their obligation - he argued - as citizens of this young nation - to be pioneers and part of that duty was to abandon the culture of the diaspora. And thus the ‘Sabra’ was born - the ‘new’ Israeli who was resilient, the Jew who would fight back against tyranny (the implication being that many Jews in Eastern Europe had gone to their deaths ‘like lambs to the slaughter’).As a result, Yiddish didn’t have an easy time in the 1950s, in the state of Israel. Many of the state’s population spoke it as their mother tongue but were embarrassed and ashamed to speak it publicly. Even worse, legislation was passed, protecting Hebrew from ‘competitor’ languages, particularly Yiddish, forbidding theatre productions to be performed and newspapers written in other languages. Additionally, diplomats and anyone else who represented Israel abroad actually had to Hebraize their names.

Many children of Holocaust survivors also recount their ‘shame’ at having parents who spoke Yiddish together, instead of Hebrew. The awful truth was that, in the 1950s, the enormity of the Holocaust was not really understood, and - as a result - many of the refugees were ‘blamed’ for not fighting back against the Nazis.

A lack of consciousness about this dark period meant that children born in Israel often ‘rejected’ their parents (and as some admit, did not want to have anything to do with their ‘old world’ language and customs). As a result of this dilemma, and the growth of modern Hebrew, today in Israel only about 3% of the population speak Yiddish on a day-to-day basis. So who are they?

View of the Jewish Cemetery on the Mount of Olives. Photo by Ria on Unsplash

Yiddish in the Haredi Ashkenazi World in Israel

Within Jerusalem is a special neighborhood, named ‘Mea Shearim’ which in Hebrew means ‘one hundred gates’ or ‘a hundredfold’. One of the oldest of the city’s neighborhoods, the people who live there are of Haredi background - that is Ultra-Orthodox Jews. Their day-to-day language of communication is Yiddish. The residents only use Hebrew for religious studies and prayer at synagogue, since they believe Hebrew is a sacred language that should only be used for communicating with God.

For any visitor to this quarter of Jerusalem, it may almost seem as if they have stepped back in time, into a world of yesteryear. Men wear black frock coats and large black hats. Women are always dressed modestly - no skirts above the knee or plunging necklines and blouses that cover the elbows. They also cover their hair, either with headscarves or wigs.

For anyone visiting this neighborhood, they will hear Yiddish on every street corner. They will also see it written in the form of ‘Pashkvils’ which are street posters, used both for political manifests and obituaries. Whilst Mea Shearim is open to all, there are large signs at its entrance (both in Hebrew and English) reminding people to behave respectfully by dressing modestly and, on Shabbat, not using their cellphones or taking photographs.

The Wailing Wall in Jerusalem's Old City, Israel. Photo by Ivan Louis on Unsplash

Preserving Yiddish Culture in Israel Today

But what of Yiddish in the rest of Israel? Well, there is, thank goodness, a more ‘happy’ side to this story - after years of it being sidelined (and ‘downgraded’) in Israeli society, there has been a resurgence in interest in the Yiddish language and culture. Today, you can attend lectures in cities across the country, given about famous writers (such as Isaac Bashevis Singer, who wrote ‘The Magician of Lublin’ and Shalom Aleichem, who penned ‘Tevye the Dairyman’).

There is a Yiddish theatre in Tel Aviv called ‘Yiddishspiel’ which was inaugurated in 1987, as a result of the campaigning of the then Mayor, Shlomo Lahat. Its mission is to restore this wonderful language (which had almost disappeared from Israel) to the public - who can learn about its charm and glory, and the extraordinarily rich culture that lay behind it. Today, it is flourishing and puts on several productions a year, which are viewed by Israelis and tourists of all ages.

Furthermore, many Israelis (especially children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors) have now signed up for Yiddish classes. Tel Aviv University has begun hosting Yiddish summer camps and the Hebrew University now offers classes for credit. Every year, in Israel, the National Authority for Yiddish Culture now gives out prizes to prominent figures in the fields of arts and literature who contribute significantly to the Yiddish language and culture in Israel.

So, what are you waiting for? Visit Israel and learn more about these two interesting languages for yourself!

People in Tel Aviv cafe, Israel. Photo by Yaroslav Lutsky on Unsplash

Login / Register

Login / Register

Contact Us

Contact Us

Certificate of Excellence

Certificate of Excellence Guaranteed Departure

Guaranteed Departure Low Prices Guaranteed

Low Prices Guaranteed 24/7 Support

24/7 Support